Harry Hay - The Communist Roots of Gay Pride

June 26, 2019

(left, Harry Hay, the father of Gay Rights, 1912-2002)

A plank of theCommunist Manifesto (1848) called for the formation of a Rothschild central bank,

not bad for a "proletarian" movement. Like a snake shedding its skin, every country with a Rothschild bank

is being inducted into a Cabalist Jewish satanic cult. (This may be the real rap against Iran: No Rothschild central bank.)

The mask of democracy is being dropped. Corporations and government are normalizing homosexuality, anathema to the Christian heterosexual foundation of Western Civilization. Just as the Communist activist Betty Friedan pioneered Feminism,another Communist organizer pioneered gay activism. In 1950, Harry Hay establishing the Mettachine Society. Ahead of his time, Hay championed NAMBLA, the North American Man-Boy Love Association.

In 1983, Hay addressed a NAMBLA conference in New York saying, "Because if the parents and friends of gays are truly friends of gays, they would know from their gay kids that the relationship with an older man is precisely what thirteen-, fourteen-, and fifteen-year-old kids need more than anything else in the world."

Now your public schools are grooming your children for this indispensable educational experience, being sodomized by an adult.

BY MICHAEL BRONSKI

(abridged by henrymakow.com)

Harry Hay--founder of the gay movement in America--who died at the age of 90 on October 24, 2002. Obits in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and the Associated Press left the impression that Hay was a passionate activist and something of a romantic. The New York Times referred to him as "an ardent American Communist, a romantic homosexual," who was a "restless middle-aged man" by the time he formed the Mattachine Society, the first gay-rights group in the United States...

The reality is that while Hay may have been a romantic, he was also notoriously promiscuous, and his communism was far more rabid than "ardent." While he did wear pearls with his longshoreman's cap, it wasn't a form of charming "gender-bender" chic, as the Los Angeles Times put it, but a political statement Hay first donned back when it was still quite dangerous to do so. Hay, in fact, was fanatically resistant to the grandfatherly image the modern gay movement not only tried to attribute to him but expected him to play out...

In 1950, when Hay formed the Mattachine Society--technically a "homophile group," since the more aggressive idea of gay rights had yet to be conceived--his radical vision was captured in a manifesto he wrote stating boldly that gay people were not like heterosexuals. Indeed, Hay insisted, homosexuals formed a unique culture from which heterosexuals might learn a great deal. This notion was at decisive odds with the view put forth by many other Mattachine members: that homosexuals should not be discriminated against because gay people were just like straight people. By 1954, the group essentially ousted Hay.

It wasn't the first time Hay had been booted out of a group he helped create. From the 1930s through the early 1950s, Hay had been an active member of the American Communist Party. In 1934, Hay and his lover Will Geer, who later played Grandpa on the long-running television series "The Waltons," helped pull off an 83-day-long workers' strike of the port of San Francisco. Though marred by violence, it was an organizing triumph, one that became a model for future union strikes--such as the one currently underway (but stymied by the Bush administration) at West Coast ports.

During the 1940s, Hay struggled unsuccessfully to be honest about his homosexuality--of which he'd been certain since adolescence--while maintaining his status as a member of the Communist Party, which banned homosexuals from joining. He married a follow Communist Party member and adopted two daughters--even as he worked to form the Mattachine Society. But homophobia eventually won out. After the Mattachine Society gained notoriety in the early 1950s, Hay was unceremoniously kicked out of the Communist Party.

The story of Harry Hay's life was that he was always just little too radical--and since he was also a bit of an egotist, too disinclined to demure--for the groups with which he was involved. He was also too idealistic. Hay took the name Mattachine from a secret medieval French society of unmarried men who wore masks during their rituals as forms of social protest. They, in turn, took their names from the Italian mattaccino, a court jester who was able to tell the truth to the king while wearing a mask.

As an old-time socialist, he was drawn to communism because of its egalitarian vision and, in the late 1930s and early 1940s, its stand against fascism. But he was also an actor and a musician drawn to a brand of scholarship that romanticized popular culture as intrinsically progressive and revolutionary. Despite, or perhaps because of, Hay's difficulty getting along with others, his vision of gay liberation was decades ahead of its time.

His monumentally important contribution to the gay movement was his ability to communicate the notion that homosexuals made up a cultural minority with its own history, political concerns, and organizational strengths. An often-told story about Hay (retold in the New York Timesobituary) recounts how he came up with a political strategy in 1948 that no one had ever voiced before: giving votes in exchange for ideological support. To wit: identity politics for homosexuals--on the same model African-Americans had begun to use in organizations like the NAACP. Hay wondered--out loud, the most basic form of political organizing--if Vice-President Henry Wallace, who was the Progressive Party's candidate for president, would back a sexual-privacy law if he could be assured that a majority of homosexuals would vote for him.

The politics of quid pro quo was revolutionary for its time. Remember, at that time it was dangerous to publicly identify as a "homosexual"--you could be arrested merely on the suspicion that you might be looking for sex; many states legally forbade serving drinks to homosexuals, much less allowing homosexuals to gather together in public. Indeed, the American Psychological Association's lifting of the definition of homosexuality as a mental illness was a good 20 years away.

Political genius that he was, Hay never would have achieved what he did without his training as an organizer for the American Communist Party. He used the party's own "cell" organization to build and propagate the ever-growing Mattachine. Even the group's recruitment tactic--it was as dangerous to walk up to someone and say, "Hey, are you a homosexual? Want to join our club?" as it was for someone to drum up membership for a seditious political group--was modelled on the Communist Party's strategy of getting names of potential members from current members.

STONEWALL

The homophile movement of the 1950s and 1960s gave way after the 1969 Stonewall riots to the Gay Liberation movement. With its roots in feminism, the Black Power movement, street culture, and the antiwar movement, the Gay Liberation movement initially appealed to Hay. It was, essentially, the movement he had envisioned in 1950 but that never came to fruition. Soon, however, Hay became disenchanted as the radical Gay Liberation movement became corporatized with groups like Gay Activist Alliance and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, whose goals were to assimilate into the mainstream rather than change the basic structures of society. Hay, yet again, was a queen without a movement...

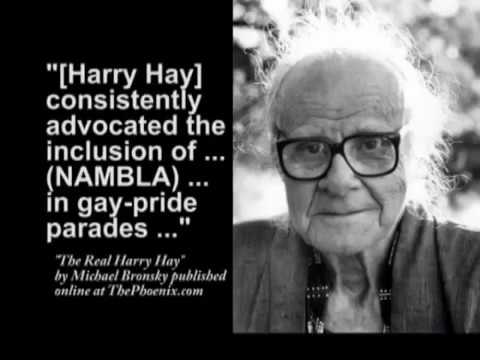

Despite his 40-year relationship with John Burnside, the aging radical still proclaimed the joys of sexual promiscuity and denounced the increasingly popular mandate that monogamy was a preferable lifestyle. In his own determined, often irritating, manner, Harry Hay resisted becoming a model homosexual hero. Nowhere was this more evident than in Hay's persistent support of NAMBLA's right to march in gay-pride parades.

In 1994, he refused to march with the official parade commemorating the Stonewall riots in New York because it refused NAMBLA a place in the event. Instead, he joined a competing march, dubbed The Spirit of Stonewall, which included NAMBLA as well as many of the original Gay Liberation Front members. Even many of Hay's more dedicated supporters could not side with him on this. From Hay's point of view, silencing any part of the movement because it was disliked or hated by mainstream culture was both a moral failing and a seriously mistaken political strategy. In Harry's eyes, such a stance failed to grapple seriously with the reality that there would always be some aspect of the gay movement to which mainstream culture would object.

By pretending the movement could be made presentable by eliminating a specific "objectionable" group--drag queens and leather people were the objects of similar purges in the 1970s and 1980s--gay leaders not only pandered to the idea of respectability but betrayed their own community.

Now Harry Hay's critics are able to do what they couldn't do when he was alive: make him presentable. The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and the Human Rights Campaign have issued laudatory press releases. (The HRC's Davis Smith says, for example, "When you were in a room with him, you had the sense you were in the company of a historic figure." A sense I certainly didn't get at a cocktail party 12 years ago, when he came across as nothing but a cantankerous old queen who was more interested in speculating about what some of the younger party guests would be like in bed than discussing the connections between 1950s communism and gay-community organizing.)

Even the Metropolitan Community Church issued a statement hailing Harry Hay's support for its work (a dubious idea at best). Neither of the long and laudatory obits in the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times mentioned his unyielding support for NAMBLA or even his deeply radical credentials and vision.

Harry, it turns out, was a grandfatherly figure who had an affair with Grandpa Walton. But it's important to remember Hay --with all his contradictions, his sometimes crackpot notions, and his radiant, ecstatic, vision of the holiness of being queer--as he lived. For in his death, Harry Hay is becoming everything he would have raged against.

Michael Bronski is a journalist, cultural critic, and political commentator. His writings have appeared in the Boston Globe, Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, and the Advocate. He is the author and editor of many books and collections, including The Pleasure Principle (St. Martin's) and Taking Liberties: Gay Men's Essays on Politics, Culture and Sex.

---

Related - Makow- The CPUSA and the Birth of Women's Liberation

------------Makow - Gays Admit They are Sick

https://www.henrymakow.com/

沒有留言:

發佈留言